It’s the question with an answer that every screenwriter, both new and old, knows but often ignores.

“Can I write camera shots in my script?”

The answer is pretty much always “No.”

It’s the exceptions that trip people up and keep this question from being resolved. So let’s first look at why you’re still seeing “camera shots” (i.e. Close Up, Tilt, Pan, etc.) in scripts that you read.

When is it Okay to Use Camera Shots?

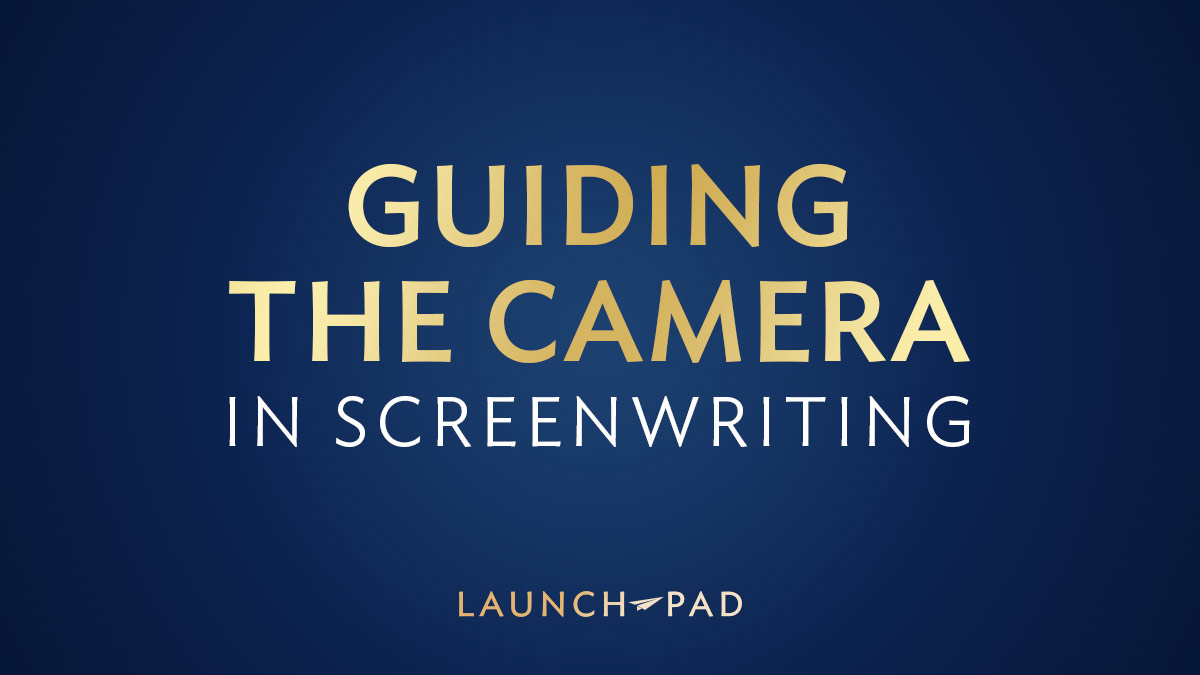

The most common reason you will see camera shots in a script is because the writer is also the director. Quentin Tarantino’s scripts are infamous for having unique prose that is just as interesting as his films, and they’re great to study as you’re developing your writing voice. He uses camera shots throughout — but no one is directing a Quentin Tarantino film other than Tarantino.

Many scripts online include camera shots, most often “ECU” (extreme close-up), or wide-shots, like you’ll see in some of Shane Black’s scripts like Lethal Weapon (he did not direct) and Kiss, Kiss, Bang, Bang (he did direct). In these two examples, Black primarily uses the direction at the beginning of the script, where he’s calling for sweeping shots of cityscapes, for a big, cinematic opening. Other times where Black directs on the page, he uses close-ups to point out something specific that comes back later on. Black, like Tarantino, is known for having a very specific writing voice in his prose.

Similarly, Black may have been working with the director and what you’re reading is the shooting script, which has gone through a pass with the director to include their notes. This is true of the Star Wars films as well, written by Lawrence Kasdan, but based on the idea by George Lucas. Kasdan has worked with some of the biggest directors in town, so no one is going to tell him how to write, and that style has been developed from working directly with people like Lucas and Steven Spielberg.

Quentin Tarantino | An excerpt from the ‘Pulp Fiction’ script

Directing Actors

Similar to camera angles, writers can become caught up in the visual details of writing, and become lost in the details of an actor’s performance. This can be a lot more challenging to avoid since what actors do on the screen should say a lot more than what their dialogue does. The best rule of thumb is to always be aware of how much space your writing is taking up on the page.

A few great examples of scripts to check out for this are Greta Gerwig’s Little Women and Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight (they each directed based on their own scripts). Both scripts show how to be economical with your prose while getting into the details of big moments.

In the first act of Little Women, the characters race from moment to moment with the energy that young adults have. But occasionally the writing style dives deeper:

Jo works with her writing costume on: an antique military jacket. Her writing is like an attack, moving into enemy territory and occupying space. Her hand starts to cramp, she shakes it, stretches it, and then switches hands.

It starts with general information about what the protagonist, Jo, is up to. But it then gets into the minutiae of what Jo does with her hands, giving us important information of her familiar moments, writing ritual, and knowledge that she is ambidextrous.

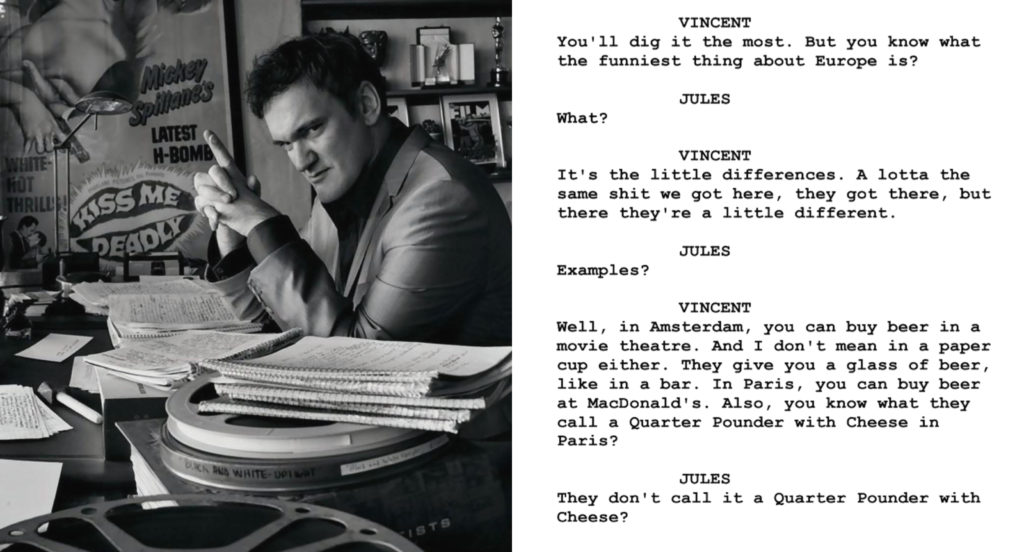

Moonlight is a deep character study, so you would expect the prose to be similarly poetic, but much of it is written very matter-of-factly. From page 28:

Paula turns from Juan, reaches into the Chrysler, pulls her pipe, a lighter from there. Holds his gaze while taking a charred, black pull.

Exhales.

An excerpt from the ‘Moonlight’ script | Barry Jenkins

There is great emotion happening, but it’s just as much in what’s not being said as it is in what is being said. The space between that quick list of actions (which invites detail shots for the camera without writing it) and then the “Exhales”, adds emphasis and weight to the moment of the entire scene. It says everything she does in as much time on the page as it will take to see it on screen.

Why You Shouldn’t Get Technical

There are a few main reasons why writers are encouraged to not be so technical. The first, and most obvious, is that your writing voice will be a lot more unique if you find creative ways to tell the camera and actors what to do without directing them. The script is the only time to establish your unique brand, so have as much fun with it as you can.

How often do you read a book and then when you watch the film or television think to yourself that’s not how I saw it when I read it… This is the second reason not to direct on the page. You want to allow the people who read your script to understand your unique voice but also see the space to help bring the vision to life. Any director is going to come in and change all the angles and actor performances you’ve included because they want their vision to be in it. They might also bring in their own writer to work with on it too.

Before the director though, you usually have to win over a producer, and they want to know where they can have an impact too. A writer who appears rigid in their style on the page doesn’t necessarily give that collaborative impression film requires.

Finally, the biggest thing about writing a feature spec is whether or not it’s commercial and producible – meaning how is the budget? If you’re focused on the details and getting lost in precious page space, anyone reading the script is going to add dollar signs for small things on screen or a special camera dolly in order to make your vision happen before anyone is attached. You can give your script a great shot but leaving space for adaptability while staying true to the story you want to tell in your voice.

How to Guide the Performance

So how do you guide the camera without mentioning the camera? Stay in frame.

This means you describe what you see only but lean into your word choice to evoke tone, color schemes, angles, distance, etc. For example, if a scene starts with a character under their car doing repairs and another car pulls up, but you want the camera to stay that initial camera — describe the dust being kicked up and clouding the person’s view, the sound of the gravel, or the splash of a puddle.

If you want a character to appear powerful, allow them to sit in the background while others pace and do the talking for them, without ever saying it’s a wide shot.

If you want the film to open with sweeping shots of Los Angeles that evoke a specific tone to set up your film, then describe Los Angeles. What time of day is it? Can you see the smog? Hear the traffic? Or is it deserted and eerily empty?

The best way to learn how to create the film you want to write is to seek out scripts, earlier drafts if possible (WGA library is a phenomenal resource if you’re in Los Angeles) and study how they did it. You’ll create a whole new style that is uniquely yours while also winning fans who want to work with someone with a clearly collaborative vision.

Want to ensure your script follows these best practices? Take a look at Launch Pad’s various coverage options!